Read the Article at Forbes.com

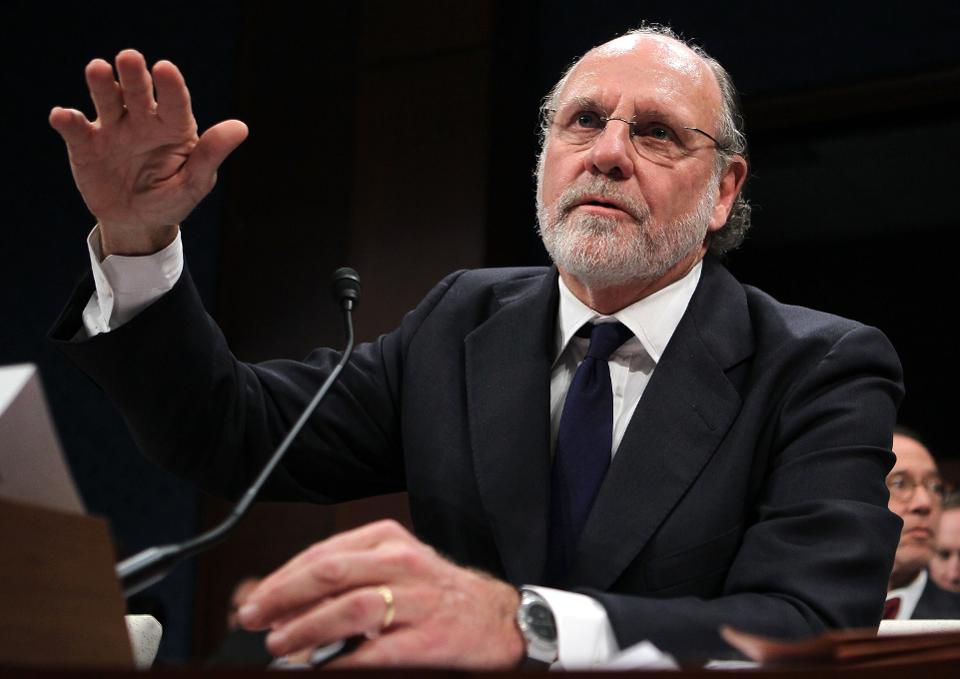

Former MF Global Chief Jon Corzine identified the villain behind the 2011 collapse of the commodities trading firm he once ran in court testimony today: Confusion. Stock investors, bond analysts, trade counterparties and banks all became convinced that a company with $14 billion in liquid assets actually was insolvent after it reported a big loss on the writedown of a tax asset and offered detailed disclosure of billions of dollars in European sovereign bonds in its portfolio.

“There was a belief the $170 million loss was a function of the Euro sovereign position,” the former Goldman Sachs partner and U.S. Senator said in a lawsuit by MF Global against its accountants, PriceWaterhouseCoopers. “The market believed that and I don’t think we were ever able to counteract it.”

One unrelated victim, at least in Corzine’s telling, was the efficient market theory. MF Global actually disclosed its European bond holdings in its quarterly and annual Securities and Exchange Commission filings, including the dollar amounts, although it relegated them to footnotes since it avoided carrying them on the balance sheet through a maneuver known as repurchase to maturity. Despite this disclosure, Corzine said, both stock investors and debt raters at Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch were surprised when MF Global provided a detailed breakdown of its holdings in October 2011 after news stories raising questions about the strategy. Within days, the company was bankrupt.

Why the market had that reaction, and whether PwC’s accounting was to blame, is the crux of the $3 billion lawsuit. The administrator for MF Global’s bankruptcy estate is suing PwC to recover money lost by its unsecured creditors, who now consist mostly of distressed-debt investors who stand to get a large payoff if the jury rules in their favor.

Corzine appeared in the 11th-story federal courtroom in downtown Manhattan this morning, a familiar figure with his bald forehead, curly gray hair and beard, and wire-rimmed glasses. He testified as a friendly witness for the plaintiffs, having already settled his own lawsuit with the MF Global administrator last year. He agreed to cooperate with MF Global and refused to cooperate with PwC. Earlier this year, he agreed to pay $5 million to settle federal charges he’d overseen the misuse of nearly $1 billion in customer deposits, at the time accepting full responsibility for MF Global’s collapse.

Profits from the trade were soon running $100 million a year, Corzine testified, providing much-needed earnings to counteract losses in its shrinking commodities trading business.

MF Global argues PwC’s accounting treatment was fatally flawed because the repo agreements ended two days before the European bonds actually matured, leaving MF Global time to regain control of them and sell, repo or buy for itself the bonds. Under some interpretations of the rules then in place, a company had to surrender all control of an asset to classify it as truly sold.

Corzine gave the plaintiffs some support by confirming MF Global could obtain repos as short as two days. PwC argues there was a three-day clearing period for bonds on the London exchange at that time so the company couldn’t do anything with them. When asked if he relied on PwC’s guidance on accounting for the RTMs, he answered “yes.”

The underlying strategy was Corzine’s however, and he testified MF Global could have put the bonds on its balance sheet with no ill effects. In fact, he said, it might have smoothed MF Global’s earnngs since the spread profit would be reported daily instead of a lump sum at the beginning of a trade. That supports the idea PwC’s advice wasn’t critical to the business strategy, but it also might support MF Global’s argument PwC’s advice steered the company toward a strategy that was riskier in terms of market perception.

Despite the footnote disclosures, the stock market and ratings firms seemed surprised when news reports surfaced about Corzine’s $6.3 billion bet on European debt in the summer of 2011. The markets were “chaotic” due to the threatened U.S. government shutdown, Corzine said, and then at the worst possible time PwC ordered the company to write down the value of deferred tax losses because their usefulness was questionable given the company’s persistent losses. The market confused the tax-loss writedown, which had no effect on cash, with rumored but untrue losses in European debt, he said.

Corzine was interrupted with repeated objections, most of them sustained by Judge Victor Marrero, when he was asked about whether debt ratings houses were surprised by the fuller disclosure of the Euro bonds. In a pre-earnings announcement meeting with Moody’s about a week before the bankruptcy they “claimed they did not know we had…” he said before being halted by the judge for straying into hearsay. Later he said “they were surprised by the European bonds,” before being stopped again.

The plaintiffs are trying to use Corzine’s testimony to illustrate but-for causation in MF Global’s demise. But for PwC’s advice on how to account for the repos and the deferred tax asset, they argue, the market would have correctly assessed MF Global’s value and the company would have survived.

Corzine did paint a picture of surprised investors and counterparties who yanked cash from the company in fear it would collapse, causing what they feared to happen. It will be the job of PwC’s lawyers tomorrow to poke holes in the idea PwC was to blame, when the essential details of Corzine’s strategy were in writing for all to see.

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images

TAFS ATTORNEYS - THOMAS, ALEXANDER, FORRESTER & SORENSEN LLP

TAFS ATTORNEYS - THOMAS, ALEXANDER, FORRESTER & SORENSEN LLP